I’m in week 2 of a 7 week on-line Coursera course titled Control of Mobile Robots, taught by professor Magnus Egerstedt of Georgia Tech. It’s an intro to control theory, as applied to mobile robots. The first week and a half has covered much of what I’ve been messing around with, so I’m holding my breath on my ability to keep up as the course moves to new stuff, especially as other activities compete for my time. The course consists of a series of video lectures and weekly quizzes. While not required for the course, there’s also a set of optional hands-on programming assignments that uses a robot simulator running in Matlab. Matlab’s not free, but you can buy a student version for $99, as being a student in online courses qualifies you for the software (you just need to email them proof of enrollment). I’ve always been curious about Matlab, so I’m checking it out.

The seven weeks will cover:

- Introduction to Control

- Mobile Robots

- Linear Systems

- Control Design

- Hybrid Systems

- The Navigation Problem

- Putting It All Together

The style is different than the Udacity classes I’ve taken, and that takes a bit of getting used to. The videos are short lectures showing the professor, with occasional videos to illustrate points and some formulas. Udacity courses, on the other hand, are like Khan Academy videos:in that they show a hand drawing on a white board rather than the professor’s face. In addition, the videos are very short segments with questions in between. I think I prefer the more interactive Q&A style, even if it’s overused on Udacity. However, the Coursera videos are only about 6-10 minutes each, with 8 or 9 videos each week, so they aren’t so long that you get bored.

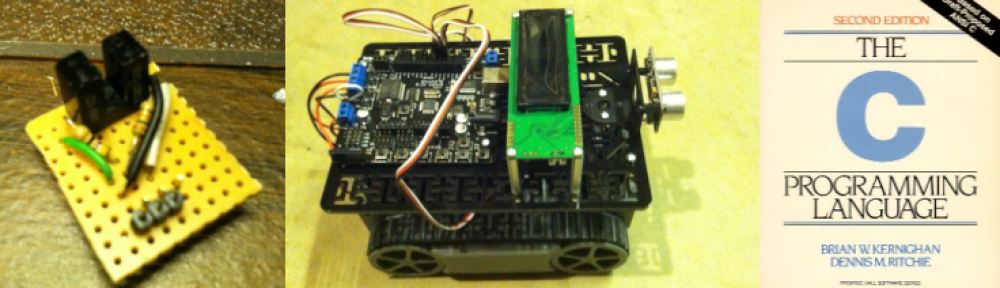

Week one provided an intro to PID control. Week two is introducing differential drive robots, odometry using wheel encoders, sensors, and an introduction to behaviors, like traveling to a goal and obstacle avoidance. I don’t know when the course will be offered again, but from what I’m seeing so far, I recommend it.