Introduction

ChatterPi is a software package that turns a Raspberry Pi into an audio servo controller. In other words, the Pi outputs commands to control a servo based on the volume of the audio input. The input can be either stored audio files (in either mono or stereo .wav format) or from an external source, such as a microphone or line level input. One of the uses is to drive animatronic props, such as a skull or a talking bird.

[This post has been updated to reflect new features added in the latest version]

Background: A Brief History of Talking Skull Control

A common prop that still makes a good impact is a talking object, whether a skull or animal. Some lower cost commercial props use a motor and spring. Another approach is to pre-program a complete sequence to match the vocals, but this is very time consuming and if you want to change the vocals, or even just edit them slightly, you need to reprogram the entire sequence. For that reason, the use of an audio servo controller to drive a servomotor controlling the jaw is a very popular approach. There are several variations. One of the earliest use hardware to detect when the audio exceeded a threshold, and then began moving the jaw towards a fully open position, and when the audio went below the threshold, it would begin closing the jaw. “Scary Terry” Simmons may have been the first to develop an electronic hardware board to do this, and Cowlacious Designs has continued to improve and sell commercial versions, with many added features such as a built in audio player, various triggering options, and the ability to control LEDs as eyes.

Later, someone named Mike (no relation) combined an Arduino with a hardware volume level board to produce the Jawduino. This went from having just 2 levels to 4. The original project just took audio in and controlled the servo, but others added extensions to play stored mp3 files and/or randomly move additional servos (for example, http://batbuddy.org/resources/Halloweenstuff/TalkingSkull.php).

A few years ago, Steve Bjork from Haunt Hackers combined dedicated hardware with a propeller microcontroller to increase the number of levels to almost 256 and also to filter out low and high frequencies that don’t tend to result in jaw movement for spoken sound. The result is the Wee Little Talker. This commercial board also has an onboard mp3 player, can be triggered externally, control LED ‘eyes,” and adds a wide array of features including a voice feedback menu system.

It occurred to me that with current single board computer capabilities and powerful software libraries, it should be possible to incorporate most of the best features of all of these into a single, software-based system running on a Raspberry Pi. The result is ChatterPi. ChatterPi was developed from scratch using the Python language, but ideas for capabilities and features were freely borrowed from previous audio servo controller projects.

Features

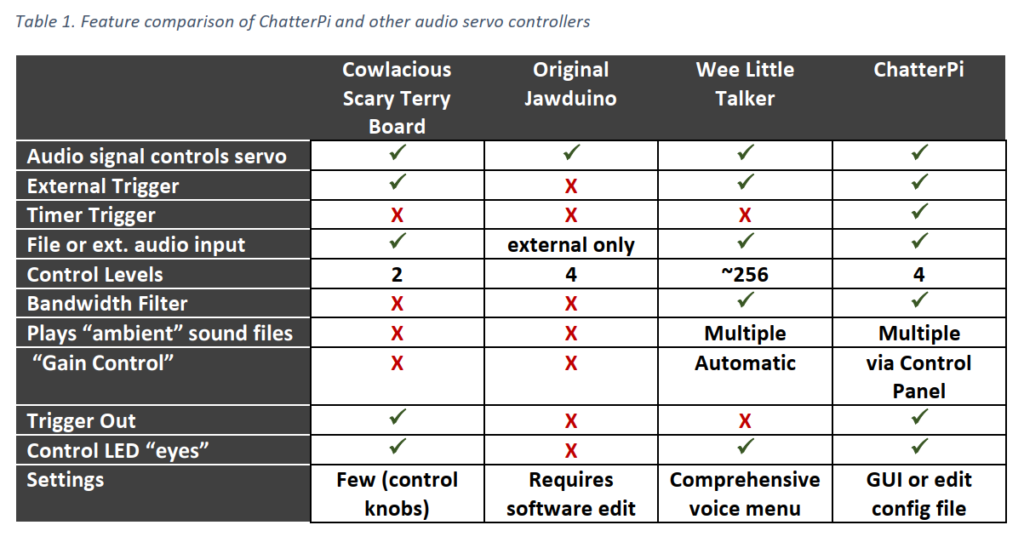

ChatterPI is designed to be extremely powerful and flexible without requiring the user to modify any of the code (although advanced users can certainly do that as well). Table 1 compares the current capabilities of ChatterPi with other audio servo controllers. The full range of capabilities and options are described in the Operations subsection.

Table 1. Feature comparison of ChatterPi and other audio servo controllers

Demonstration Video

Demonstration Video

This video shows ChatterPi in action, using both a saved .wav file and microphone input. ChatterPi is controlling the jaw movement. The other skull movements are pre-programmed as a script running on a Pololu Maestro Servo Controller.

Using ChatterPi

This section describes how to set up and install both the hardware and software for using ChatterPi, and for using it.

Hardware

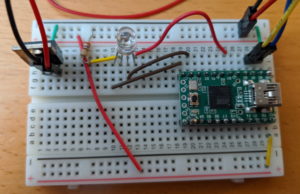

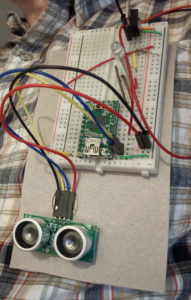

ChatterPi was developed and tested on a Pi 3 A+ and a Pi Zero W. It should work on any Pi. [Originally it ran too slowly on a Pi Zero. A section of code for analyzing audio volume used list processing and a loop. This code was replaced using Numpy, and it’s now fast enough to work on a Pi Zero.]

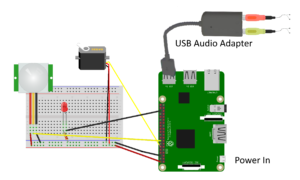

In addition to the Raspberry Pi, you’ll ]need a USB sound card. This is needed for several reasons. First, if you plan to use an external sound source, you need a way to get audio into your Pi. Second, besides not producing very good sound, the audio out connector may share timing with the Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) code that is needed to drive the servo, creating conflicts. Use of an inexpensive USB sound card solves both issues. I’ve used one from Adafruit that sells for less than $5 and works well (see https://www.adafruit.com/product/1475). You will need TRS (standard stereo) plugs or an adapter to go into the headphone and microphone jacks on the sound card. The card does not work with a TRRS (combination microphone / stereo headphone plug. You only need a microphone or other external sound source if you wish to use one. Otherwise you can use audio .wav files that you save on the Raspberry Pi. You still need the USB sound card for audio output, however.

That’s all you need for the audio servo controller. Of course, you’ll need a power supply and a servo that you want to control, such as a servo-equipped talking skull, and a passive infrared sensor (PIR) if you want to trigger your prop using one. I used this one (https://www.parallax.com/product/555-28027) from Parallax for development, as I had a spare one already. ChatterPi can also be set to trigger off of a repeating timer or to just turn on and run if you don’t want to use an external sensor.

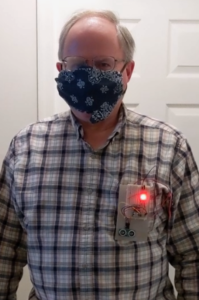

Figure 1 shows a test bench setup for testing operation. The Red LED is attached to the “TRIGGER_OUT” pin for testing purposes. It can be moved or another LED and resistor attached to the “EYES_PIN” to test that feature. The TRIGGER_OUT pin goes high for 0.5 seconds when the controller is triggered. This can be used to trigger another prop or controller. The EYES_PIN stays high for as long as the audio plays.

The default PIN selection (which can be changed in the config.ini file) are:

- Jaw servo: 18

- PIR input trigger: 23

- Trigger out: 16

- Eyes: 25

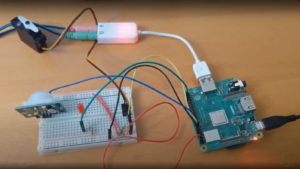

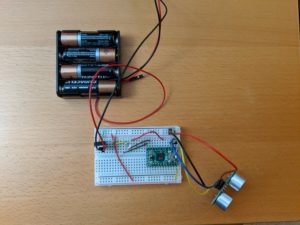

Figure 2 is a photograph of my test setup. The placement of the wiring on the breadboard is slightly different because I was using it to test a variety of items and also a 3-wire servo controller wire, but the schematic connections are identical.

Software Overview

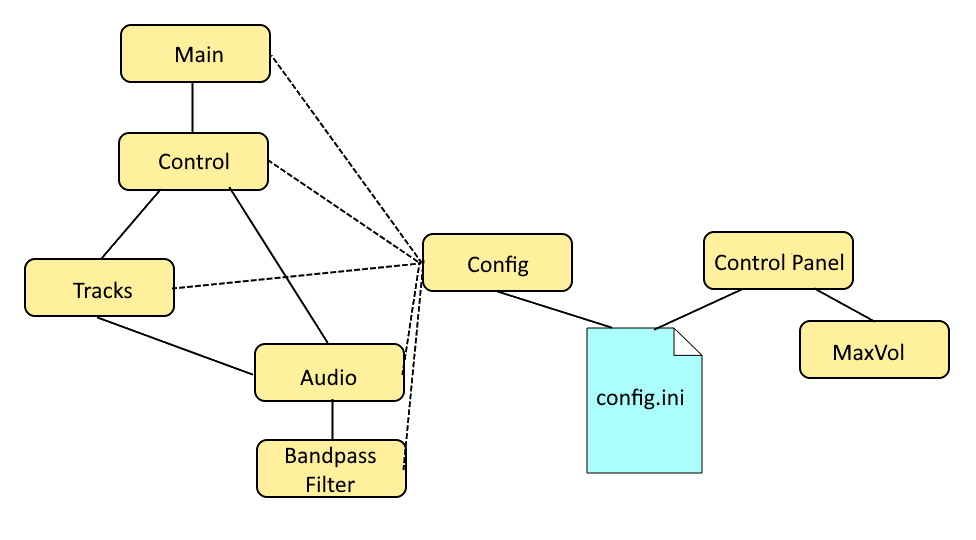

Knowledge or understanding of the software code is not required to operate or use the ChatterPi. The ChatterPi package consists of eight Python 3 modules and one configuration file, as shown in Figure 3.

The configuration file, config.ini, holds all of the user selectable parameters, including which pins are used for which functions, whether the audio source is the microphone input or stored .wav files, which servo control mode should be used, and the servo threshold levels. The config.py program simply reads these values and makes them available in memory during runtime.

The main.py program essentially simply loads the configuration parameters on start-up and calls control.py. The functions in control.py are not folded into main.py in order to avoid a submodule having to import the main program, which can be problematics.

Most of the processing occurs in the control.py and audio.py modules. The control.py program handles most of the triggering (either a timer, an external trigger such as a PIR, or immediately upon startup, with the method specified in the config.ini file. It uses the GPIO Zero and PiGPIO libraries to monitor the triggering sensor and send output to the output trigger and led pins. PiGPIO is used as the GPIO layer underneath GPIO Zero because it uses DMA control for the Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) control used to the control the servo. Some other libraries, including the default one used by GPIO Zero, use software PWM, which is adequate for tasks such as controlling the brightness of LEDs, but not precise enough for servo control.

Unless the triggering mode is START, the file enters an infinite loop waiting for either a timer to expire (TIMER mode) or the external trigger to be generated (PIR mode). The wait functions meet the requirements and during development, interrupt driven approaches interfered with the audio output, probably due to timing conflicts. In TIMER mode, the timer is restarted after either the audio file finishes playing (if the source is FILES) or after a configurable pre-set time (if the source is MICROPHONE).

When triggered, an event handler is called that, depending upon the settings, sets off the TRIGGER_OUT to trigger another prop or device and turns on the LED eyes or other low power device. Then, if the audio source is FILES, it will call tracks.py, which will select the next .wav file to be played and call audio.py, passing the name of the .wav file to be played. If the audio source is MICROPHONE, audio.py is called without passing a file name. When the call to audio.py returns, the event handler turns the LED eyes off and returns.

Audio playback, audio analysis, and servo control are all performed by the audio.py module. It defines one class, AUDIO. When the audio.play function is called, it checks on whether the audio source is MICROPHONE or FILES and opens a PyAudio stream appropriately. The stream call runs in a separate thread (this is automatically handled by PyAudio). For each chunk of the input stream, a callback function is called. This callback function is where the audio stream volume is analyzed. The average volume for each chunk is calculated, and the servo is commanded to the appropriate position based on that average volume and the threshold levels that the user has specified in the config file. The wave library is used to read the wave files from storage, and the struct library is used to help deconstruct the wave data to calculate volume and to help to separately analyze the left and right channels for stereo files. The number of levels, the specific thresholds, and whether a bandpass filter is applied before calculating the volume is based on the STYLE setting set by the user in the config file. In addition to the official documentation, I found a slide presentation, Introduction to PyAudio, by Jean Cruypenynck to be very helpful.

If the STYLE is set to 2, then bandpassFilter.py is called to process the digital audio stream and return a modified stream with the bandpass filter applied. The program is very short and simple. It uses two functions from the scipy signal processing library to filter out audio input below 500 Hz and over 2500 Hz. No bandpass filter is applied for STYLE 0 or STYLE 1.

When AMBIENT is set to ON, the ambient playback function in audio.py must also monitor for triggering events (either the timer or sensor), since it needs to interrupt itself and pass control back to control.py when such an event occurs.

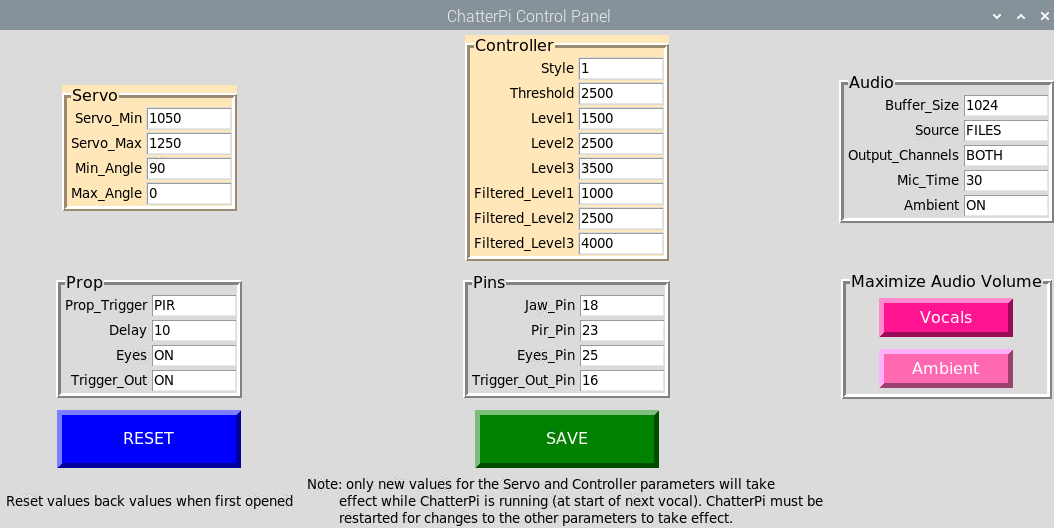

The config.ini file can either be edited directly or through a GUI program named controlPanel.py. If the servo or controller subset of parameters are changed during execution, the changes will be reflected the next time a vocal track is triggered. Other changes will not take effect until after ChatterPi is stopped and then restarted.

maxVol.py is a utility program that can be launched from the control panel. It reads and analyzes each wave file in either the vocals or ambient subdirectories and writes them back with the volume levels increased to the maximum possible without clipping or distortion.

Software Installation, Setup, and Operations.

See the User’s Manual on GitHub for complete instructions. UPDATE: In addition to the source code, there’s now a Pi SD card image file available for download, so you won’t have to do any installations of dependencies or the source code, just install the image on a micro SD card, load it up in your Pi, and your ready to go! See the link in the README file at GitHub – ViennaMike/ChatterPi.

Project Roadmap

This version, 0.9, includes all the features currently planned for ChatterPi. That said, there are two additional features that might be added at a later time (or if anyone cares to add them to this open source project:

- The ability to use .mp3 files. Simply playing MP3 files on a Raspberry Pi is easy, but they must be processed in real-time as a stream to drive the servo controller.

- Add drop down pick lists for many of the options in the control panel, and allow lower case values to be entered, auto-correcting to upper case.

- Add the ability to start and stop the execution of ChatterPi from the control panel.

Wrap Up

The code is open source and published on GitHub (https://github.com/ViennaMike/ChatterPi), and I would welcome anyone who wanted to work on adding any of these advanced features.

To report a bug, make a suggestion, or ask a question, please go to the GitHub repository for the project (https://github.com/ViennaMike/ChatterPi) and open an Issue. To do so, first click on the issues tab, and then use the green “New Issue” button. It’s a good idea to first browse through or search other reported issues to see if someone has already reported the same issue or asked the same question. You can then add comments or suggestions to existing issues, rather than opening a new, duplicative issue.